Read my interview with the author on the All The Light We Cannot See book. Discover the Anthony Doerr books in order and details on the new Netflix TV series.

This exclusive interview with acclaimed author Anthony Doerr delves into the captivating world of Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize-winning All the Light We Cannot See book.

Join me as Doerr offers unique insights into the creation of this literary masterpiece, revealing the inspirations, challenges, and emotions that brought this unforgettable tale to life.

Be sure to scroll down to see the FULL LIST of books from the author, and more details on the All the Light We Cannot See movie.

All The Light We Cannot See Summary

In this story, Marie-Laure lives with her father in Paris near the Museum of Natural History, where he works as the master of its thousands of locks.

When she is six, Marie-Laure goes blind, and her father builds a perfect miniature of their neighborhood so she can memorize it by touch and navigate her way home.

When she is twelve, the Nazis occupy Paris, and father and daughter flee to the walled citadel of Saint-Malo, where Marie-Laure’s reclusive great-uncle lives in a tall house by the sea.

They carry what might be the museum’s most valuable and dangerous jewel with them.

Meanwhile, in a mining town in Germany, the orphan Werner grows up with his younger sister, enchanted by a crude radio they find.

Werner becomes an expert at building and fixing these crucial new instruments, a talent that wins him a place at a brutal academy for Hitler Youth, then a special assignment to track the resistance.

More and more aware of the human cost of his intelligence, Werner travels through the heart of the war and, finally, into Saint-Malo, where his story and Marie-Laure’s converge.

All the Light We Cannot See Themes:

This novel was selected for an Alex Award which is given to ten books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults, ages 12 through 18.

You will find many powerful themes in this book including:

War and Its Impact: The novel vividly portrays the devastating effects of World War II on individuals, families, and communities. It poses moral dilemmas faced by characters caught amid the conflict.

Resilience and Survival: The story follows the journeys of two young protagonists, Marie-Laure and Werner, as they navigate the challenges of war. Their resilience, courage, and determination to survive against all odds highlight the strength of the human spirit.

Human Connection: Amidst the chaos of war, the novel emphasizes the importance of human connections and empathy. It explores the bonds formed between characters, emphasizing the capacity for kindness and compassion even in the darkest times.

The Power of Knowledge: The novel celebrates the transformative power of knowledge and the way it can provide solace and hope. Marie-Laure’s love for books and Werner’s expertise in radio technology are symbolic examples of the intellectual pursuits that can illuminate even the darkest paths.

Moral Choices: Throughout the story, characters are faced with moral dilemmas and choices that challenge their values and principles. These ethical quandaries reflect the complexities of human nature and the blurred lines between right and wrong during times of war.

At the time of this interview, Anthony Doerr had already been on the New York Times best-seller list for twenty weeks. He certainly doesn’t need this interview for a promotion.

Shortly after my interview, they awarded All the Light We Cannot See the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction and the 2015 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

The Best Anthony Doerr Books (Exclusive Author Interview)

What was it like spending a decade on this book, and did you ever feel discouraged while writing it?

Oh, I was crazy with doubt almost of the time.

You invest so many months into a single project—shelves stuffed with WWII books, three separate trips to Europe, dozens of scribbled notes, and the terror that you won’t be able to pull it all together keeps you up at night.

I worried that if I abandoned the project, I’d let down my wife, kids, editor, and myself.

And I never dreamed it would take so long—a quarter of my life!

The story beautifully centers around radio communication bringing unlikely individuals together. What inspired your choice to delve into radio, and did researching older radio models and their workings play a significant role in crafting this plotline?

I adored radios as a boy and often stayed up late listening to baseball games under my covers while my parents thought I was sleeping.

But that passion had waned until ten years ago, when I took a train from Princeton, New Jersey, into New York City.

I had just completed a novel and was searching for a new idea, and I had a notebook in my lap.

The man in the seat in front of me was talking to someone on his cell phone about the sequel to The Matrix, I remember that very clearly, and as we approached Manhattan, sixty feet of steel and concrete started flowing above the train, his call dropped.

And he got angry!

He started swearing and rapping his phone with his knuckles, and after briefly worrying for my safety, I said to myself: What he’s forgetting, what we’re all forgetting, is that what he was just doing is a miracle.

He’s using two little radios — a receiver and a transmitter — crammed into something no bigger than a deck of cards to send and receive little packets of light between hundreds of radio towers, one after the next, miles apart, each connecting to the next at the speed of light, and he’s using this magic to have a conversation about Keanu Reeves.

Because we’re habituated to it, we’ve stopped seeing the grandeur of this breathtaking act.

So I decided to write something that would help me and my reader feel that power again, to feel the strangeness and sorcery of hearing the voice of a stranger, or a distant loved one, in our heads.

That very afternoon, ten years ago, I wrote a title into my notebook: All the Light We Cannot See—a reference to all the invisible wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum (like radio waves).

And that night, I started a piece of fiction in which a girl reads a story to a boy over the radio.

I conceived of her as blind and him as trapped in darkness, and the sound of her voice, carried by radio waves – the light we cannot see — through walls, as his salvation.

My heart went out to Werner, especially during his time in the Hitler Youth and the difficult choices he had to make for survival.

The book delves into themes of death, war, sadness, and poverty, despite the underlying hope in the story’s conclusion. Writing about this challenging period in history must have been tough.

Can you share which scene was the most challenging for you to write?

Yes, lots of the research for this novel was excruciating.

The destruction of human beings during WWII, especially on the Eastern Front, occurred on a scale almost too large for the human brain to comprehend.

Sometimes, the source material would send me to dark places, and I’d have to take breaks to work on other projects.

As for scenes that were hard to write, a writer faces many kinds of difficulties: technical, emotional, and syntactic.

In terms of emotions, all the scenes involving Frederick were the most difficult because he reminds me of one of my sons.

Marie-Laure’s father’s intricate puzzles add so much beauty to your story.

It made me wish I could find a puzzle for my kids to solve.

How did you come up with this concept?

A friend of our family once gave me a Japanese puzzle box as a present.

It was a wooden cube that looked like an ornate, solid block of wood. No visible doors, no knobs, no handles, no buttons.

But, as our family friend showed me if you knew what side to push in on, then various panels would start to slide down, and by manipulating all the panels in clever ways, you could eventually slide open the top and discover a hidden compartment inside.

I played with that thing for hours, showing it off to friends, examining its construction, etc., then eventually put it on a shelf and forgot about it.

A couple of decades later, while working on this novel, the puzzle box came back to me, along with my fascination with it, and I decided to try writing a couple of scenes in which Marie-Laure’s father fashions puzzle boxes.

Which character do you identify the most within your book?

I do my best to identify with all my characters, even the bad actors—I think that’s probably part of the job description for any novelist, isn’t it?

This novel has 187 chapters beautifully segmented and sectioned for the reader in small doses. Why did you decide to structure your story this way?

Obviously, there are infinite ways to write a novel, but for me, “plotting it out” has always sounded scary and programmatic.

I have to compose, revise, and re-revise scenes to understand what should happen.

So my process involves a lot of trial and error. I write hundreds of paragraphs trying to figure out where the story is going, and I usually cut most of them.

I knew early on that I wanted the two narratives to feel like two almost parallel lines that gently inclined toward each other.

The structure was a big mess for a long time.

It probably had 250 or 300 chapters at some points.

All I knew early on — and wanted a reader to intuit – was that Marie’s and Werner’s lives would intersect.

But it took me a long time to figure out exactly how that would happen.

If you could tell anyone to read one book (other than your own), what would that book be?

Oh, gosh, my answer to this question changes all the time, but a novel I’m absolutely in love with right now is Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

It’s about family, siblinghood, memory, storytelling, and particularly about our society’s treatment of animals.

It’s also structured in this beautiful, organic, perfect way—I hope a few of your readers will look at it!

*Editor’s Note: Read my interview with Karen Joy Fowler about “We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves” here!

Frequently Asked Questions About Anthony Doerr Books:

How do you pronounce Anthony Doerr?

Anthony Doerr’s last name sounds like “door.” For a pronunciation guide, it would look like this: Anthony Dor

What are the best Anthony Doerr books?

My favorite book by the author is All the Light We Cannot See.

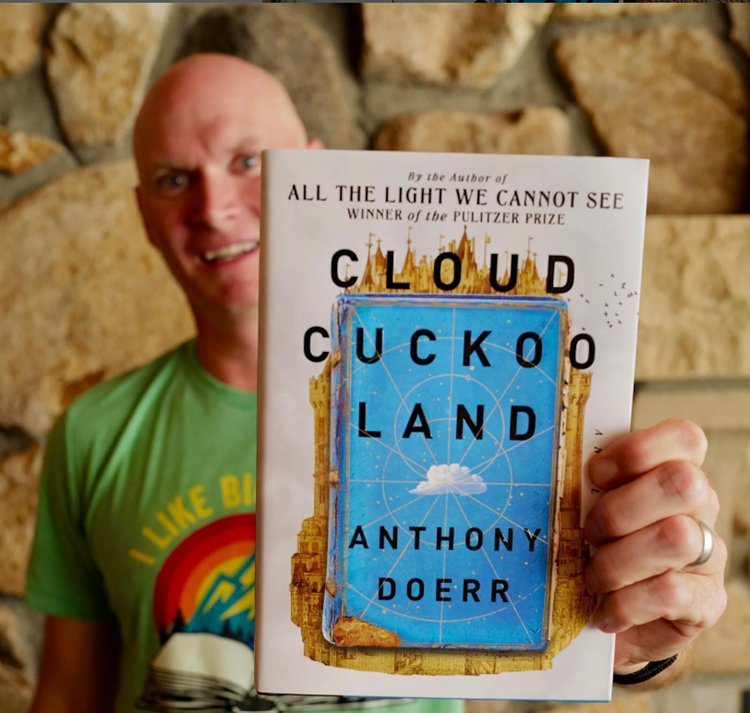

This novel also is the highest-rated on GoodReads, followed closely by Cloud Cuckoo Land.

Is All The Light We Cannot See based on a true story?

All The Light We Cannot See is a work of historical fiction.

While the characters are entirely fictional, the setting of Saint-Malo is a real place.

When can I watch All The Light We Cannot See movie?

The book will become a Netflix TV series very soon!

Directed by Shawn Levy, the Netflix adaptation stars Louis Hofmann, Lars Eidinger, Marion Bailey, Hugh Laurie, Aria Mia Loberti, and Mark Ruffalo.

With four hour-long episodes in total, the All the Light We Cannot See limited series will premiere on November 2, 2023, nearly a decade after the novel was published.

You can watch the riveting movie trailer here!

What are Anthony Doerr’s books in order published?

- The Shell Collector: Stories (2001)

- About Grace (2004)

- Four Seasons in Rome: On Twins, Insomnia, and the Biggest Funeral in the History of the World (2007)

- Memory Wall: Stories (2010)

- All The Light We Cannot See (2014)

- Cloud Cuckoo Land (2021)

Love this author interview? Stream the Book Gang Podcast wherever you get podcasts. We discuss debuts, backlist, and under-the-radar book gems with your favorite authors.

TELL ME: What is your favorite Anthony Doerr book?

Pin It